FNS regularly conducts research and data analysis to inform program or policy decisions and understand nutrition program outcomes. In addition, FNS seeks to make data accessible to state and local agencies, service providers, and the public by developing data visualization and analytics tools that can be used to support nutrition program delivery or report on outcomes.

The below data visualization and analytics products bring together FNS, USDA, and other federal datasets to answer questions related to food security, nutrition assistance programs, and the systems that support them. Dashboards include “about” or “information” pages to answer questions about navigation, interactive functionality, data sources, and the data transformations that have been applied.

National and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and Program Reach in 2023

This report, the latest in an annual series, presents 2023 national and state-level estimates of the number of people eligible to receive benefits provided through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and the percentage of the eligible population and the general U.S. population participating in the program.

The number of people eligible for WIC in 2023 remained about the same as the year prior.

- The estimated average monthly WIC-eligible population totaled 11.83 million in calendar year (CY) 2023 (Table 1), essentially unchanged from the estimate of 11.79 million in 2022.

- In 2023, about half of infants and children and more than one third of pregnant women in the U.S. were eligible to participate in WIC.

| Participant Category | Number Eligible | Percent of Total Eligible (%) | Total Population | Eligibility Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 1,796,821 | 15.2 | 3,600,389 | 49.9 |

| Children | 7,626,138 | 64.5 | 14,713,756 | 51.8 |

| 1-year-old children | 1,883,018 | 15.9 | 3,672,400 | 51.3 |

| 2-year-old children | 1,914,319 | 16.2 | 3,668,357 | 52.2 |

| 3-year-old children | 1,937,138 | 16.4 | 3,619,422 | 53.5 |

| 4-year-old children | 1,891,664 | 16.0 | 3,753,577 | 50.4 |

| Women | 2,406,255 | 20.3 | 6,615,976 | 36.4 |

| Pregnant women | 1,091,474 | 9.2 | 2,791,608 | 39.1 |

| Postpartum women | 1,314,781 | 11.1 | 3,824,368 | 34.4 |

| Breastfeeding women | 848,829 | 7.2 | 1,995,462 | 42.5 |

| Non-breastfeeding women | 465,952 | 3.9 | 1,828,907 | 25.5 |

| Total | 11,829,215 | 100.0 | 24,930,121 | 47.4 |

In 2023, WIC reached 56% of those who are eligible – the highest coverage rate since 2016.

- The percentage of the eligible population participating in WIC is known as the coverage rate.

- In an average month in 2023, WIC served an estimated 56.1% of those eligible for WIC (Table 2), up from the estimate for 2022 (53.5%), and the highest coverage rate since 2016.

- The increase in the coverage rate resulted from the negligible change in the number of individuals eligible for WIC combined with a significant increase in participation. WIC participation increased by around 320,000 in CY 2023, an increase of about 5% over the year prior.

| Characteristic | Number Eligible | Number Participating | Coverage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 11,829,215 | 6,631,309 | 56.1 |

| Participant Category | |||

| Infants | 1,796,821 | 1,479,155 | 82.3 |

| Children | 7,626,138 | 3,656,078 | 47.9 |

| 1-year-old children | 1,883,018 | 1,268,459 | 67.4 |

| 2-year-old children | 1,914,319 | 1,004,346 | 52.5 |

| 3-year-old children | 1,937,138 | 874,822 | 45.2 |

| 4-year-old children | 1,891,664 | 508,450 | 26.9 |

| Pregnant women | 1,091,474 | 538,332 | 49.3 |

| Postpartum women | 1,314,781 | 957,744 | 72.8 |

| Breastfeeding women | 848,829 | 600,628 | 70.8 |

| Non-breastfeeding women | 465,952 | 357,117 | 76.6 |

| Race and Hispanic Ethnicitya | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 4,341,509 | 2,865,239 | 66.0 |

| Black-only, not Hispanic | 2,477,494 | 1,308,652 | 52.8 |

| White-only, not Hispanic | 3,742,399 | 1,840,027 | 49.2 |

| Two or more races or other race, not Hispanic | 1,238,566 | 602,318 | 48.6 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, not Hispanic | 243,653 | 112,539 | 46.2 |

| Asian, not Hispanic | 619,026 | 285,804 | 46.2 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, not Hispanic | 74,125 | 46,583 | 62.8 |

a See report “Table 3.1 WIC coverage rate by participant characteristics” for detailed definitions of race and ethnicity categories used in the report.

Coverage rates varied by participant category and characteristics – continuing to be highest for infants and decreasing as children age.

- In 2023, coverage rates were highest for WIC-eligible infants (82.3%) and postpartum non-breastfeeding women (76.6%), while the coverage rates for WIC-eligible children (47.9%) and pregnant women (49.3%) continued to be lower than other participant categories.

- The relative differences in coverage rates by participant category remained mostly consistent from CY 2005 to CY 2023. Across all years, coverage rates were highest for infants, followed by coverage rates for postpartum women. Coverage rates for children were consistently the lowest (except for 2022, when the coverage rate for pregnant women was the lowest).

- In recent years, coverage rates for pregnant women have declined more rapidly than for other participant categories, declining from 53.0% in 2018 to 49.3% in 2023, despite a small increase in coverage rates for pregnant women between 2021 and 2023.

- The estimated coverage rate for WIC-eligible individuals in metropolitan areas in the average month of 2023 was 61.1%, while the coverage rate for WIC-eligible individuals in nonmetropolitan areas was 24.0%. Of the 11.83 million individuals eligible for WIC, an estimated 10.21 million lived in metropolitan areas in 2023.

A large share of Medicaid and SNAP participants do not participate in WIC despite being eligible.

- Consistent with previous findings, large percentages of Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients who were eligible for WIC did not participate in WIC in 2023.

- Among WIC-eligible Medicaid participants, 32.0% participated in WIC.

- Among WIC-eligible SNAP participants, 57.6% participated in WIC.

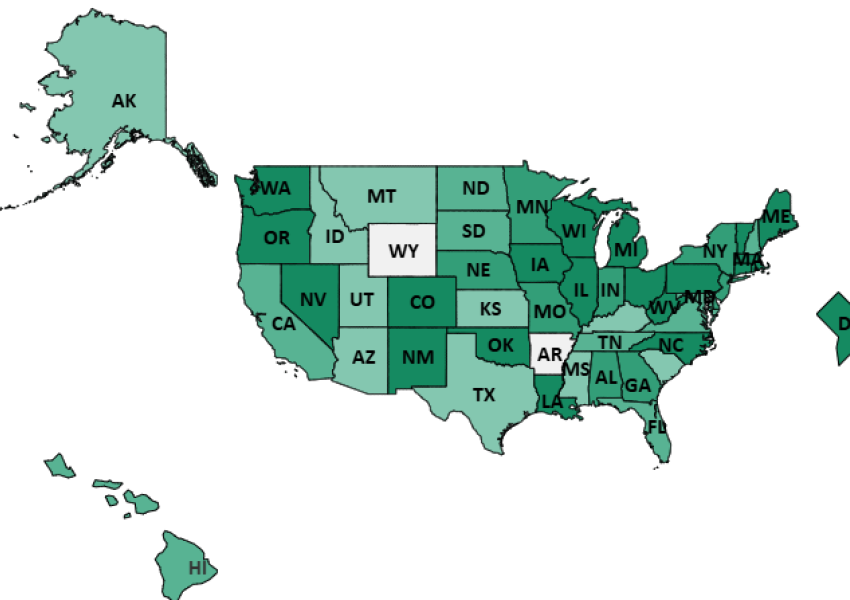

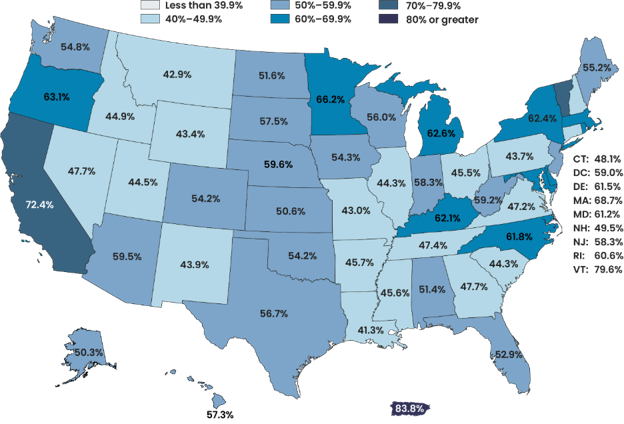

Coverage rates vary substantially by state.

- Coverage rates vary substantially by state, as shown in the map below (Figure 1), ranging from around 40% in some states to more than 70% in others.

- Coverage estimates are less precise for states with small populations compared to other states (see Figure 3.5 in the full report); therefore, differences between states and across years may be less pronounced than they appear in the map.

Why FNS Did This Study

WIC provides healthy foods, breastfeeding support, nutrition education, and referrals to other services to eligible pregnant, breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding (up to six months after the end of pregnancy) postpartum women, infants, and children up to age 5.

WIC funding is provided by Congress through the annual appropriations process. Since approximately 1997, Congress has funded WIC at a level sufficient for the program to serve all eligible applicants. WIC funding needs are estimated annually using the number of individuals eligible for WIC and the percentage of the eligible population likely to participate. We allocate funds to participating state agencies based on a formula that considers the previous year’s funding and the estimated eligible population in each WIC state agency, along with other factors. Accurately estimating the number of individuals eligible for WIC and the number likely to participate enables us to better predict future funding needs, measure WIC performance, and identify potentially unmet nutrition assistance needs.

This report presents estimates of the numbers of women, infants, and children eligible for WIC during an average month in 2023 and historical estimates for 2016–2022. This is the most recent report in a series that provides eligibility estimates at the national, regional, and state levels. Estimates are also provided by participant category—infants, children, pregnant women, and postpartum women—and by race and ethnicity, urbanicity, and reported household income.

How FNS Did This Study

We calculated the estimates for this study on a methodology developed in 2003 by the Committee on National Statistics of the National Research Council.1 The 2023 estimates continue to incorporate methodological improvements first described in the 2021 report.2 These methodologies use data from various sources, including the Community Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC), American Community Survey (ACS), and National Vital Statistics. The estimates presented in this report use the same methodology as and are consistent with the 2022 WIC eligibility estimates published in 2024.3

1 Ver Ploeg, M., & Betson, D. M. (Eds.). (2003). Estimating eligibility and participation for the WIC program: Final report. The National Academies Press.

2 Kessler C., Bryant A., Munkacsy, K., and Gray K. (2023). National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2021. Prepared by Insight Policy Research, Contract No 12319819A0005. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support, Project Officer: Grant Lovellette. Available online at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eer/2021.

3 Kessler C., Bryant A., Munkacsy, K., and Gray K. (2024). National- and State-Level Estimates of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2022. Prepared by Insight Policy Research, Contract No 12319819A0005. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support, Project Officer: Grant Lovellette. Available online at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eer/2022.

Suggested Citation

Kessler C., Bryant A., Munkacsy K., Maxson S., Ressler D., Saluja R., and Farson Gray K. (2025). National- and State-Level Estimates of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2023. Prepared by Westat, Contract No. GS-00F-009DA/140D0424A0040, Order No. 140D0424F1045. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Project Officer: Grant Lovellette. Available online at: www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eer/2023.

This report, the latest in an annual series, presents 2023 national and state-level estimates of the number of people eligible to receive benefits provided through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and the percentage of the eligible population and the general U.S. population participating in the program.

Proposed Rule - Updated Staple Food Stocking Standards for Retailers in SNAP

Summary

In response to section 765 of the Consolidated Appropriation Act of 2017 and subsequently enacted appropriations, this rule proposes to codify a new framework for determining distinct staple food varieties and accessory foods (such as snacks, desserts, and foods meant to complement or supplement meals, which do not themselves count as staple foods) for purposes of meeting the staple food requirements for retailer participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The rulemaking is necessary to implement the codified stocking requirements of the Agricultural Act of 2014, which increased the minimum number of staple food varieties and perishables SNAP retailers must carry. A summary of this notice of proposed rulemaking is posted on regulations.gov.

Request for Comments

Comments must be received by Nov. 24, 2025.

The Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), USDA, invites interested persons to submit comments on this proposed rule. Comments may be submitted by one of the following methods:

- Federal e-Rulemaking Portal: Go to regulations.gov. Preferred method; follow the online instructions for submitting comments on docket FNS-2025-0018 or enter “RIN 0584-AF12” and click the “Search” button. Follow the instructions at this website.

- Mail: Comments should be addressed to SNAP Retailer Policy Division, Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, 1320 Braddock Place, Alexandria, Virginia 22314.

All comments submitted in response to this rulemaking will be included in the record and will be made available to the public. Please be advised that the substance of the comments and the identity of the individuals or entities submitting the comments will be subject to public disclosure. FNS will make the comments publicly available on the internet via: regulations.gov. We encourage commenters to include supporting facts, research, and evidence in their comments. When doing so, commenters are encouraged to provide citations to the published materials referenced, including active hyperlinks. Likewise, commenters who reference materials which have not been published are encouraged to upload relevant data collection instruments, data sets, and detailed findings as a part of their comment. Providing such citations and documentation will assist us in analyzing the comments.

Supplementary Information

Background

The Agricultural Act of 2014 (2014 Farm Bill) amended the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 (herein referred to as “the Act”) to increase the number of staple food varieties that certain SNAP authorized retail food stores must have available on a continuous basis in each of four staple food categories. The standards were increased from requiring a minimum of three (3) varieties to seven (7) varieties in each of the four (4) staple food categories and increased the number of varieties that must be perishable from one (1) variety in each of two (2) different staple food categories to one (1) variety in each of three (3) different staple food categories.

The Department promulgated regulations to implement the increased breadth of stock requirements in the final rule, “Enhancing Retailer Standards in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)’’ (81 FR 90675), published on Dec. 15, 2016 (the “2016 final rule”). That rule also outlined what constituted a variety in all four staple food categories. However, after the regulations were finalized, section 765 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2017 and provisions in subsequent appropriations acts have in effect prohibited the Department from implementing, administering, or enforcing the retailer ‘‘Breadth of Stock’’ and “Variety” provisions of the 2016 final rule until the Department makes regulatory modifications to the definition of ‘‘variety’’ that would increase the number of food items that count as acceptable staple food varieties for purposes of SNAP retailer eligibility. To meet this directive, the Department published a proposed rule, “Providing Regulatory Flexibility for Retailers in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)” (84 FR 13555) on April 5, 2019. An overwhelming majority of the almost 9,000 comments received were opposed to the provisions as arbitrary and confusing and many argued the provisions would impact SNAP households’ access to a variety of healthy food options and make it easier for fraud-prone retailers that do not primarily sell food to enter the program. Additionally, the 2019 proposed rule did not incorporate specific criteria described in the preamble into proposed regulatory text. Supportive comments, from retail food stores and industry groups, generally advocated for more flexibility overall. For these reasons, and because of the length of time that has passed since comments were received, the Department is issuing this new proposed rule to solicit fresh comments on a new proposed framework to determine distinct staple food varieties that would be codified in regulatory text. The Department also proposes to add and codify food categories that count as accessory foods, which are generally considered snacks or dessert foods or are meant to complement or supplement meals. Accessory foods do not count towards meeting the staple food stocking or sales requirements for retailer eligibility. While the “Accessory Food Items” provision of the 2016 final rule did go into effect, the specific criteria that determined what qualifies as an accessory food were not incorporated into regulatory text but were, instead, implemented through agency guidance Retailer Policy Management Division Policy Memo 2020-05 and SNAP Accessory Foods List. USDA is now proposing to codify, with modifications, these two guidance documents. This proposed rule does not modify any other provisions or components of the 2016 final rule.

Breadth of Stock

In order to be eligible to participate in SNAP, a retail food store must meet either Criterion A (staple food stock) or Criterion B (staple food sales) requirements under SNAP regulations at 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii) and (iii), respectively. Most stores are authorized under Criterion A, which requires a minimum breadth of staple food stock in each of the four staple food categories, which are (1) meat, poultry, or fish; (2) dairy; (3) bread or cereals; and (4) vegetables or fruits. Specialty food stores, such as butcher shops or fruit and vegetable stands, are typically authorized under Criterion B, which requires that at least 50% of a store’s gross sales be for staple foods in at least one staple food category. Currently, (pursuant to the conditions of Section 765 of the 2017 appropriations language Act and the repeated conditions in subsequent appropriations language) stores authorized under Criterion A must carry at least three (3) varieties of staple foods in each of the four (4) staple food categories where at least one (1) variety in at least two (2) staple food categories is perishable. For each variety, stores must carry at least three (3) stocking units. Upon finalization of a new staple food variety framework through this rulemaking, the SNAP retailer stocking requirements in Section 3(o) of the Act would also go into effect because the conditions of the appropriations language will have been satisfied. Those stocking requirements, which have already been codified at 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii) but not enforced, would require SNAP retailers to stock seven (7) varieties of staple foods in each of the four (4) staple food categories, of which at least one (1) variety in each of three (3) different staple food categories is perishable. The requirement to carry at least three (3) stocking units for each variety, as currently implemented and codified in regulations, will remain the same. The increased number of staple food varieties required under Criterion A is non-discretionary. While this proposed rule would not make any changes to the minimum breadth of stock stores are required to carry, this part of the previously codified standards would be implemented for the first time upon publication of a final rule under this rulemaking.

Definitions of Accessory Food, Prepared Food, Retail Food Store, and Staple Food

The Department proposes to remove the discussion of accessory foods, variety, and main ingredient from the “Staple Food” definition at 7 CFR 271.2 for greater clarity. Instead of addressing all four terms in one definition, this proposed rule would add a separate definition for “Accessory Food.” The definition of main ingredient and the expanded frameworks for staple food varieties and accessory foods would be codified separately at 7 CFR 278.1(b). In line with the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), 2020-2025, the definition of “Staple Food” at 7 CFR 271.2 would indicate that the meat, poultry, or fish staple food category would be referred to as the protein category to be inclusive of high protein plant-based food—and it will be referred to as, simply, the protein category through the remainder of this proposed rule. Similarly, the bread or cereals category would be referred to as the grains category to be inclusive of other grain-based food products—and it will be referred to as, simply, the grains category through the remainder of this proposed rule. The current definition of “Staple Food” already accounts for plant-based options for both the protein and the dairy categories. The proposed changes to streamline the definition of “Staple Food” would not result in any substantive changes to the definition or to existing staple food categories as currently defined.

To prevent inconsistency, the Department also proposes to remove the discussion of criteria A and B and prepared food from the definition of “Retail Food Store” in 7 CFR 271.2, Criterion B is currently outlined in 7 CFR 278.1(b)(iii). Criterion A would be outlined in greater detail at 7 CFR 278.1(b)(ii), and a separate definition for “Prepared Food” would be added to 7 CFR 271.2 through this proposed rulemaking.

Finally, the Department proposes to move out of the “Retail Food Store” definition, the criteria for determining which co-located businesses are evaluated as a single firm for purposes of determining retailer eligibility. Instead, the provision would be added as new subparagraph at 7 CFR 278.1(b)(8). The proposed reorganization of provisions currently included as part of the “Retail Food Store” definition would not result in any substantive regulatory changes.

Application of Criterion A

Reorganization

For purposes of greater clarity and readability, as well as to incorporate a more detailed framework for determining distinct staple food varieties when assessing SNAP retailer eligibility, the Department proposes to reorganize 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1). Specifically, this rule proposes to remove redundancy in subparagraph (A) of 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(i) and break up subparagraph (A) of 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii) to address, in separate subparagraphs, the staple food stocking standards and the requirement to display the required stock for sale on a continuous basis. This action does not make any substantive changes to the current regulations. While this proposed reorganization highlights the statutory increases in the required number of varieties in each staple food category, those non-discretionary standards were already codified by the 2016 final rule, though these requirements have never been enforced due to Section 765 of the 2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act and the repeated conditions in subsequent appropriations language. If this rule were to be finalized as proposed, it is the Department’s view that the requirements of this appropriations language would have been met and thus would negate the need for continuation of this appropriations language.

Staple Food Varieties

In this rulemaking, the Department is faced with balancing several competing interests, including ensuring that SNAP retailers carry a larger variety food options, that retailer food stores can easily understand the requirements, that the requirements can be operationalized in an efficient and cost-effective manner, and that the variety framework does not undercut Congress’ intent to make the stocking standards more rigorous so that unscrupulous retailers are not able to gain entry into SNAP for the sole purpose of defrauding the program (H.R. Rep No. 113-333, 2014). In a December 2018 report, SNAP: Actions Needed to Better Measure and Address Retailer Trafficking, the General Accountability Office (GAO) reiterated its 2006 finding that the minimal requirements for the amount of food that retailers must stock could allow retailers more likely to traffic SNAP benefits (i.e., referring to the illegal exchange of SNAP benefits for cash or consideration other than eligible food) into the program. It is with all these interests in mind that the Department proposes a modified framework for distinguishing food items that would count as distinct varieties. As a result, the Department believes that the new approach described below is superior to the 2016 construct precisely because it more effectively balances all the competing interests.

Specifically, the Department proposes to codify the framework for determining distinct varieties at 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C). In general, this proposed rule would maintain the overall current framework but proposes two new groups of distinct varieties for operational simplification and to give more weight to traditional staple food products. The Department believes that this approach is superior to the 2016 structure because it will provide more options for retailers to meet the variety requirements under this new staple food framework than under the 2016 framework.

To date, the criteria for determining which foods count as distinct staple food varieties (different types of food within a staple food category) have existed only in agency guidance and have generally been defined based on the type of food (by each different plant or animal) or the main ingredient of the food product. For the protein and vegetables or fruits staple food categories, this generally means that different types of food—regardless of brand, packaging, flavoring, style or cut, etc.—count as one distinct variety. For example, all types of apples fall within one variety separate from all types of oranges, just as all forms of chicken fall within one variety separate from all forms of beef. For the dairy and grains categories, this generally means that different types of products—even those that have the same main ingredient—are distinct varieties. For example, yogurt is a distinct variety from cheddar cheese, even if they both have milk as the main ingredient; and bread is a distinct variety from pasta, even if they both have wheat as the main ingredient. More recently, FNS has counted plant-based dairy alternatives as distinct dairy varieties from the traditional mammal-based varieties for each different type of plant the product is made from (e.g., almond milk is a separate variety from soy milk and both are separate varieties from cow’s milk) and counted dairy products from different mammals as distinct traditional dairy varieties (e.g., cow milk is a separate variety from goat milk). For multi-ingredient food products, long-standing agency policy has determined variety and category by the main ingredient, defined as the first listed ingredient after water, stock, or broth. For example, if a can of beef stew has beef as its main ingredient, it counts as a beef variety in the protein category.

With the non-discretionary increase in the number of varieties SNAP retailers will be required to stock in each staple food category, retailer stakeholders have expressed concern with being able to meet the new standards, particularly for the dairy and the protein categories. An analysis of 121,294 SNAP-authorized small format retail food stores (which represent 64% of all SNAP-authorized small retailers, or 45% of all SNAP-authorized retailers) determined that, in terms of meeting the higher number of staple food varieties required by the 2014 Farm Bill, 81% of the small stores already stocked enough grains and 83% already stocked enough fruits and vegetables, while only 63% already stocked enough protein and only 52% already stocked enough dairy.

Staple Food Subgroups 1 and 2

In general, the more varieties that are subdivided based on main ingredient or other factors (such as dairy or meat fat content, whole or refined grains, and cheese firmness), the more difficult the system becomes to operationalize and the more costly it becomes for FNS to identify and document the distinct varieties. It can also become more confusing for retail food stores, making it difficult for them to meet the stocking standards simply because they do not understand the requirements. Currently, FNS employs a contractor to take photos of store aisles to get a sense of the overall store inventory, but not individual items or their ingredients. When retailers are at the margin of eligibility, and the availability of certain inventory is not clear or needed information is not on the front of the packaging, follow-up store visits or documentation requests are required to determine whether the store has sufficient stock. Such situations increase the time it takes for a retailer to become authorized. To make the variety criteria more straightforward and minimize the need to identify the main ingredient for basic food products, the Department proposes to establish two separate subgroups of staple food varieties.

In group 1 under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(1), the specific types of raw food identified, without any other ingredients, would count as separate varieties from multi-ingredient food products with the same main ingredient. The purpose of this group is to promote the stocking of basic staple food essentials needed for the home preparation of meals rather than counting such essentials as the same variety as multi-ingredient, processed foods with the same main ingredient. The Department proposes to include the following three types of food in group 1:

- Grain-Based Flour;

- Raw Grains; and

- Dry Beans, Peas, or Lentils.

For example, as part of group 1, the following foods, which currently count as just one variety, would be separate varieties under the proposed framework:

- Cornmeal and ears of corn or a product with corn as the main ingredient;

- A bag of uncooked rice and canned soup with rice as the main ingredient; and

- A bag of dry beans and canned cooked beans.

All dry beans, all dry peas, and all dry lentils, regardless of the kind of bean, pea, or lentil, each would count as one distinct variety, for a total of 3 possible varieties, separate from any multi-ingredient product with beans, peas, or lentils as the main ingredient. The same construct would apply to each kind of grain for grain-based flour and raw grain. Therefore, instead of a bag of raw rice, rice flour, and a frozen grain bowl with rice counting as one rice variety as is currently the case, each of those items would count as its own distinct variety under the proposed framework. The same would apply for each different type (e.g., oats, barley, wheat etc.).

In group 2, under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(2), the specific types of food identified would count as only one distinct variety, regardless of different main ingredients or coming from different animals or plants. The purpose of this group is to make the process of identifying distinct varieties as simple and intuitive as possible for both FNS and retailers while still meeting the intent of the program to provide SNAP households with access to a broad range of staple food varieties to meet their nutritional needs. This framework is currently being applied through longstanding practice to specific dairy and grains products as indicated in agency guidance, SNAP Staple Foods. Through this rulemaking, the Department proposes to codify the framework and the specific products for which it applies. This rule also proposes to count additional dairy subproducts as distinct varieties and count tofu/tempeh as a distinct variety of protein. At the same time, the current practice of subdividing bread by various forms (such as bagels, sliced bread, tortillas, pita, etc.) would be eliminated. The Department proposes to include the following 17 different types of food products in group 2:

- Eggs

- Bread

- Perishable Liquid Milk

- Shelf-Stable Liquid Milk

- Dried or Powdered Milk

- Fermented or Cultured Dairy Beverages

- Yogurt (non-liquid)

- Butter

- Cream (separate from butter)

- Cheese

- Perishable Meat, Poultry, or Fish (for each different kind of animal)

- Shelf-Stable Meat, Poultry, or Fish (for each different kind of animal)

- Tofu/Tempeh

- Infant Formula

- Infant Cereal

Unlike the foods in group 1, most of the foods in group 2 are available in multiple forms, with a wide array of main ingredients. As a result, the main ingredient of many food products listed in group 2 cannot be easily determined by just looking at the product or even knowing what kind of product it is. Breakfast cereals, for instance, may each have a different grain (such as corn, oat, or wheat) as the main ingredient. Under the proposed framework, all breakfast cereals would fall within one variety, regardless of the grain from which they are made. The same construct would apply to all the food products in group 2, greatly simplifying the process for determining if a retail food store meets the standards for Criterion A.

The Department is aware that the proposal to no longer subdivide bread by its form (e.g., rolls, baguette, sliced bread) may be controversial. However, the Department has concluded that counting each form of bread as a distinct variety is not practical given the need to categorize a large number of possibilities. Allowing a retailer to meet the stocking requirement for the grain category with just bread also subverts the purpose to require retail food stores authorized under Criterion A to carry a broader variety of staple foods in each staple food group. By separating out certain foods as distinct varieties through the combination of food items identified in both groups 1 and 2, the Department would be replacing those varieties with other, more basic varieties of grains which are easier to distinguish and are commonly stocked in retailer food stores of various types and sizes. For example, under the new proposed framework, rice products could be counted in as many as three distinct varieties: rice flour, rice grain, and any other product with rice as the main ingredient. Currently, all these products count as only one “rice” variety. By singling out these specific food products, the new variety framework would not only make it easier for FNS to determine retailer eligibility, but it would also make it easier for retailer food stores to more accurately determine if they meet the stocking requirements before deciding to move forward with applying for authorization.

Plant-Based or Grain Alternatives to Dairy Products

Plant-based alternatives are currently recognized as distinct varieties from the traditional dairy products for which they are a substitute. Under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(3)(i), the Department would maintain this provision but proposes to limit the number of plant-based alternatives that may count towards the dairy category to three. Current policy does not limit the number of plant-based dairy alternatives that a single retail food store may count towards meeting the staple food stocking requirements in the dairy category. For example, having sufficient units of almond milk, oat milk, and soy milk is enough to meet the current dairy stocking requirement. Yet, the DGA states that, other than fortified soy milk, no other plant-based dairy alternative contains the nutritional content to meet the dietary recommendations for dairy. This proposed change would help ensure that SNAP retailers carry a variety of milk, yogurt, and cheeses rather than meeting the standard through multiple varieties of plant-based milks.

Under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(3)(ii), the Department proposes to move several high protein plant foods from the vegetable or fruit category, for which almost all retail food stores already carry a sufficient number of varieties, to the protein category. Under this proposed rule, the following types of foods would count as protein: nuts and seeds, beans, peas, and lentils. This proposed change would not only add more protein varieties, but it would also properly encourage retail food stores to carry plant-based proteins and help meet the nutritional needs of SNAP households through high-fiber protein sources, particularly for individuals with plant-based diets. The Department does not propose limiting the number of plant-based varieties that may count in the protein category because the DGA includes a broad group of foods from both animal and plant sources in the protein category, which can help individuals meet the protein dietary recommendations.

Appropriations Directive

In accordance with enacted appropriations directing USDA to increase the number of items that qualify as acceptable varieties in each staple food category the proposed variety framework would create several more varieties in the protein, dairy, and grains categories than existed in the 2016 final rule. The vegetables or fruits category already includes numerous possible varieties—significantly more than any other staple food category. Furthermore, 83% of currently authorized small format stores already stock enough fruits and vegetables. Any further attempts to subdivide existing vegetable or fruit varieties would add unwarranted complexity to a category that, up to this point, has always been the most straightforward. Therefore, the Department does not propose any changes to the vegetables or fruits staple food category. However, because there has been some confusion as to whether pre-cut fruits and vegetables were considered prepared food for retailer authorization purposes, the Department would like to take this opportunity to clarify that cold pre-cut fruits and vegetables intended for home consumption count as a staple food in the vegetable and fruits category. Therefore, bags of sliced apples or broccoli florets continue to count as a staple food. In addition, the Department is proposing to codify, with modification, the definition of “Prepared Foods” in current agency guidance, “Retailer Eligibility- Prepared Foods and Heated Foods,” to allow cold pre-cut food intended for home consumption, even if cut by the retailer on the premises of the firm, to count as staple food as long as the retailer has not otherwise prepared the food for immediate consumption. This means that a bag of shredded lettuce to prepare a salad at home, regardless of whether the lettuce was shredded on the premises of the store, counts as a staple food. Shredded lettuce and other cold cut fruits or vegetables from a salad bar from which the customer must prepare their own salad by serving themselves would also count as staple food. However, if the retailer serves, mixes, and/or otherwise prepares the ingredients of the salad for the customer, even if cold, then the salad would continue to be considered prepared food that does not count towards meeting the SNAP staple food stocking or sales requirements.

As discussed earlier, carrying enough varieties in the protein and dairy categories has historically presented the biggest challenge for small format retail food stores when it comes to meeting the staple food stocking standards for SNAP authorization followed by the grains category. Therefore, the Department would like to specifically address the additional varieties the new proposed framework would create in each of those three staple food categories in comparison to the 2016 final rule. We note that the number of different groupings of varieties indicated does not reflect the total number of possible distinct varieties under that staple food category. For example, although the protein category has seven categories of varieties, there are numerous possible distinct varieties under the single “perishable meat, poultry, or fish” category because each kind of animal (e.g., cow, pig, lamb, turkey, chicken, trout, flounder) represents a separate variety, all of which would be impossible to fully identify or count.

Protein Category

The Department is proposing to subdivide protein into the following seven groupings of varieties:

- Perishable meat, poultry, or fish, including fresh or frozen versions for each different kind of animal;

- Shelf-stable meat, poultry, or fish for each different kind of animal;

- Eggs;

- Nuts/seeds;

- Raw beans, peas, or lentils, each of which would count as a distinct protein variety;

- Cooked (e.g., canned) beans,

- Peas, or lentils and multi-ingredient products with beans, peas, or lentils as the main ingredient; and

- Tofu/tempeh, together, would be a distinct variety from all other types of proteins and any other pea product as the main ingredient.

As with the 2016 final rule, this rule would add nuts/seeds as well as beans, peas, or lentils to the varieties FNS currently counts in the protein category, adding an additional 4 possible protein varieties—(1) nuts/seeds; (2) beans; (3) peas; and (4) lentils. In addition, this rule would add the last four varieties listed above to the varieties established by the 2016 final rule, allowing for numerous additional possibilities for each type of shelf-stable meat, poultry or fish, as well as three additional varieties each for beans, peas, or lentils in its raw form, and one additional variety for tofu/tempeh, which would be separate from any other product with soybeans or other peas as the main ingredient.

Dairy Category

The Department proposes to subdivide dairy into twelve distinct categories:

- Perishable liquid milk (such as whole milk, 2% milk, 1% milk, skim milk, etc.) for each different type of mammal;

- Shelf-stable liquid milk, such as canned evaporated or condensed milk and boxed milk;

- Cheese;

- Yogurt (non-liquid);

- Butter;

- Infant formula;

- Cream (other than butter, which would continue to be its own separate variety), such as heavy cream, sour cream, and half and half;

- Fermented or cultured dairy beverages, such as kefir, buttermilk, and yogurt-based drinks;

- Dried milk, such as milk powder; and

- Plant-based alternative (for up to three different dairy products listed above).

Current agency guidance counts all milk products, other than the first five products listed above, as one single “milk” variety. Under the 2016 final rule, cheese was further subdivided into soft cheese and hard/firm cheese, and milk was further subdivided into perishable and shelf-stable milk, adding two additional dairy varieties.

In agency guidance issued in April 2023, Criterion A - Stocking Requirements for Retailers: Dairy, FNS made dairy products distinct varieties for each different type of mammal (e.g., cow milk, sheep milk, goat milk) to make the distinctions for mammal milk more similar to that for plant-based dairy alternatives. Prior to this policy change in 2023, milk was one variety, regardless of the mammal it came from, while plant-based dairy alternatives were counted as separate varieties for each different kind of plant it was made from (e.g., soy milk, coconut milk, rice milk). However, such distinctions for mammal-based milk have proven to be difficult to operationalize. Feta cheese, for instance, can be made from various kinds of milk either by itself or in combination, including goat milk, sheep milk, and cow milk, making it almost impossible to determine the dairy variety without looking at the ingredients list. While the proposed framework would eliminate this recently added distinction for dairy products by mammal for the types of products listed in group 2, the four additional dairy varieties under the proposed framework are common types of dairy products that most retail food stores carry. Not only is it less likely for small format retail food stores to carry most of these products for any mammal other than cow, essentially making the distinction by mammal immaterial, it would streamline the retailer approval process by eliminating the need to identify which type of mammal milk is the main ingredient of each of those products. Under the proposed framework liquid perishable milk would continue to count as distinct varieties for each type of mammal.

In this rule, the Department proposes to carry over the 2016 provision of making shelf-stable dairy a distinct variety from perishable dairy. However, for the reasons stated above, the Department has reconsidered counting soft cheese and hard/firm cheese as two separate varieties and distinguishing dairy products, other than liquid milk, by mammal or, in the case of plant-based alternatives, by main ingredient as the 2016 final rule had. Instead, this proposed rule would add three different distinct dairy varieties in the form of cream, fermented or cultured dairy beverages, and dried milk. Therefore, cream and fermented beverages would count as a distinct variety from milk or yogurt, and dried milk would count as a distinct variety from liquid shelf-stable milk. The operational difficulties of determining which animal a product is made from or the main ingredient of a plant-based alternative, which include numerous possibilities, would impose an undue burden on the agency as discussed earlier. The Department is also proposing these changes based on retailer industry feedback indicating that counting plant-based dairy alternatives and dairy made from mammals other than cows as distinct varieties would not significantly assist small-format stores in meeting the increased SNAP stocking requirements in the dairy category since such products are note widely in demand by customers of small-format stores.

Grains Category

The Department proposes to subdivide grains into six distinct categories:

- Raw Grains for each different type of grain;

- Flour (grain-based) for each different type of grain;

- Bread;

- Pasta/Noodles;

- Breakfast Cereals/Foods (such as a box of corn flakes, frozen waffles, or pancake mix); and

- Infant Cereal.

For the grains category, the 2016 final rule subdivided bread into five varieties based on the bread form. The five varieties included bread, bagels, buns/rolls, English muffins, and pitas for each type of grain. The Department believes that such categorization introduces too much confusion as to which category a particular bread form falls under. For example, it is unclear how tortillas or croissants would be categorized. Likewise, it is unclear how cornbread or matzo bread would be categorized. Also, determining the grain each bread is made of would present significant operational challenges for a construct that is counter to the Congressional intent to require a greater range of different types of food in each staple food category.

Under this rule, the Department now proposes to count all bread as one variety, regardless of form or the grain from which it is made. However, for each type of grain, the Department proposes to count raw grain as a separate variety from any other product with that grain as the main ingredient and to count flour as a separate variety from the raw grain or any other product made with the same gain. Raw grains and flour, which are not only generally more easily identifiable on account of having the grain clearly indicated on the front of the package, are also important components for the preparation of numerous foods.

Finally, the Department proposes to combine both the cold and “hot” cereal varieties with the baking mix variety included in the 2016 final rule. However, the category would be expanded to include other breakfast foods, such pre-made frozen/cold waffles, pancakes, etc. With the introduction of raw grains and flour as distinct varieties for each type of grain, the Department believes that having three separate varieties for breakfast foods is not only unnecessary but would add unwarranted complexity by requiring varieties to be based on whether it is intended to be eaten hot or cold as well as whether it is ready-to-eat or not. Also, the Department believes that having a baking mix variety would not, in most cases, add additional possibilities. Baking mixes for dessert foods (such as cakes, brownies, cookies, etc.) would be considered accessory foods that do not count towards the staple food stocking requirements even if the main ingredient is flour. Also, any baking mix that has an accessory food as the main ingredients would also be an accessory food. Therefore, having a separate baking mix variety would give the false impression that any baking mix counts as a separate variety in the grains category, leading to both retailer confusion and operational ambiguity.

In the end, the Department has determined that the addition of raw grains and flour for each type of grain more than makes up for the removal of the of other distinct grain varieties while staying true Congressional intent. Under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(4)-(5), the Department proposes to codify existing long-standing policy. Current policy prohibits counting a food product in more than one staple food category. Current policy also does not count a single type of food that is packaged differently as distinct varieties. For example, chicken wings and chicken breasts are both currently counted as one “chicken” variety. Similarly, ground beef and chuck roast are both currently counted as one “beef” variety. A single type of food that is prepared differently is also not currently counted as separate varieties. For example, whole fresh tomatoes, 100% tomato juice, and tomato sauce all currently count as one “tomato” variety. Similarly, pork loin and pork hotdogs are both currently counted as one “pork” variety. Different flavorings also do not currently count as distinct varieties. For example, chocolate milk and plain milk both currently count as one “milk” variety. Finally, different kinds of the same type of food also do not count as distinct varieties. For example, brown rice, wild rice, and white rice all currently count as one “rice” variety. Similarly, mandarin oranges, tangerines, and navel oranges all count as one “orange” variety. These current policies would remain unchanged in this proposed rule.

Under 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C)(6), the Department proposes to also codify the long-standing definition of “main ingredient” currently used to determine the staple food category and variety of a food product with multiple ingredients. “Main ingredient” is currently defined as the first listed ingredient unless the first ingredient is water, stock, or broth. If the first ingredient is water, stock, or broth, the next ingredient is considered the main ingredient for determining the variety of staple food or whether it is an accessory food. This definition is based on the Food and Drug Administration requirement that ingredients be listed from highest to lowest quantity by weight in the ingredients list on the product’s label (21 CFR 101.4). The definition would remain unchanged in this proposed rule.

Accessory Food

In accordance with section 3(q)(2) of the Act, and as currently codified at 7 CFR 271.2 (definition of “Staple Food”) and 7 CFR 278.1(b)(1)(ii)(C), accessory foods do not count towards meeting the retailer staple food stocking or sales requirements discussed above. The current definition of “Staple Food” at 7 CFR 271.2 also defines accessory foods as foods that are generally considered snacks or desserts and/or are meant to complement or supplement meals and provides several illustrative examples for each of the two groups. Agency guidance, SNAP Accessory Foods List (March 5, 2018), provides several more examples and states that any food product that is not specifically identified as an accessory food in agency guidance shall be considered a staple food. In an effort to further the purpose of the program to provide low-income households access to nutritious food essential to health and well-being, as well as to meet the intent of Congress to reduce fraud at retail stores by requiring more rigorous staple food stocking standards, the Department is taking this opportunity to update the current accessory foods list and to codify it through this proposed rulemaking.

Under this proposed rule, the Department would separate the current list of accessory foods by creating a third group ̶ edible items primarily used as part of the food preparation process. Most of the foods that would be listed under this group are already included in the current accessory foods list under one of the other two existing groups. Additional specific examples would be added for clarity and consistency, including yeast, starch, broth, stock and gelatin. These items are subproducts of currently listed items and considered accessory foods under long-standing agency practice. This clarification would also be consistent with the definition of “main ingredient,” which is the first ingredient listed in the ingredient list of food product after broth, stock, or water. Water is already explicitly identified as an accessory food, as is bouillon. These proposed changes would not have any material impact on current practice.

The Department also proposes adding three new groups of foods to the accessory food list. The proposed new groups are:

- Snack bars, including but not limited to, protein, granola, and baked bars. Such food products are not generally eaten as a meal, but as a snack between meals. Furthermore, because multi-ingredient food products are categorized by the main ingredient, snack bars may fall under any one of the four staple food categories. This makes it difficult to categorize snack bars by looking at the package itself and leads to counterintuitive classification, such as a protein bar that has whey as the main ingredient counting as a staple food in the dairy category.

- Jerky, other than whole-muscle meat jerky, including but not limited to beef jerky and plant-based jerky. While jerky is rich in protein, non-whole muscle jerky is also typically eaten as a snack between meals. Counting jerky as a staple food also allows stores to meet the protein staple food category by merely stocking jerky sticks of different animals, such as beef jerky, turkey jerky, and pork jerky, which are currently counted as three separate protein varieties. This classification of jerky does not further the purposes of the program or the intent of Congress for SNAP retailers to be required to carry a broader variety of foods in each staple food category. Changing jerky to an accessory food may also compel SNAP retailers to stock alternative food varieties that would count under the protein staple food category.

- Cheese or fruit dips and spreads, including but not limited to, cheese sprays, jams, jelly, marmalade, preserves and compote. Cheese or fruit dips and spreads are meant to complement or supplement a meal, which the Act explicitly identifies as a category of accessory foods. In addition, cheese dips and spreads are highly processed cheeses made with less real cheese and more additives. Similarly, fruit spreads tend to be high in sugar content, which is not foundational to a balanced diet.

The Department recognizes that many individuals may occasionally or frequently eat some of these food products as meal replacements. These proposed changes, however, would not prevent households from purchasing these food items with SNAP benefits. All accessory foods, while not counted as staple foods for retailer eligibility purposes, are generally eligible for SNAP purchase. 1

1 With approval by the Secretary for a demonstration project waiver, authorized by Section 17 of the Act, states may restrict the purchase of certain foods with SNAP benefits. For additional information, see SNAP Food Restriction Waivers.

This rule proposes to codify a new framework for determining distinct staple food varieties and accessory foods for purposes of meeting the staple food requirements for retailer participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

FD-162: Public Posting of TEFAP Information

| DATE: | September 9, 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| POLICY NO: | FD-162: The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) | |

| SUBJECT: | Public Posting of TEFAP Information | |

| TO: | Regional Directors Supplemental Nutrition Programs | State Directors All TEFAP State Agencies |

Under the leadership of Secretary Brooke Rollins, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) is committed to strengthening strategies to encourage healthy choices, healthy outcomes, and healthy families, along with clarifying program requirements for our state agency partners. In support of these goals, this memorandum provides guidance to TEFAP state agencies on requirements for public posting of TEFAP information at 7 CFR 251.4(l). Each state agency must post a list of eligible recipient agencies (ERAs) that have an agreement with the state agency on a publicly available webpage. In addition, state agencies must post the state’s uniform statewide eligibility criteria on a publicly available webpage. The public posting of ERAs and uniform statewide eligibility criteria must be implemented by Oct. 31, 2025. State agencies are encouraged to implement these provisions before that deadline.

ERAs that have an Agreement with the State Agency

TEFAP regulations at 7 CFR 251.4(l) require each state agency to post a list of ERAs that have an agreement with the state agency on a publicly available webpage. At a minimum, this list must include the name, address, and contact telephone number of all ERAs that have an agreement with the state agency. State agencies must update this list annually but are encouraged to update it more frequently as needed.

FNS recognizes that state agencies may identify a compelling public safety reason to forgo posting an ERA address publicly; for example, for a domestic abuse shelter. In such circumstances and without divulging sensitive or confidential information, the state agency should submit general information to their FNS regional office regarding why the location should be exempted from the publicly available list posted online. FNS will work with state agencies on a case-by-case basis for ERAs in this situation.

State Agency Option to Post Additional ERA Information

State agencies may choose to exceed the above minimum posting requirements to support public awareness. While state agencies are not required to post information about ERAs that have agreements with other ERAs, states have the option to publish this information online. State agencies may also choose to include additional information about ERAs on the webpage, such as operating hours, the areas served by the ERA, links to ERA websites, and distribution site addresses. In addition, state agencies may develop tools to aid eligible individuals in accessing the program, for example by establishing a searchable tool to identify aid based on zip code.

Posting TEFAP Statewide Eligibility Information

TEFAP regulations at 7 CFR 251.5(b) require each state agency to establish uniform statewide criteria for determining the eligibility of households to receive USDA Foods for home consumption, including requirements for demonstrating income and residency. Per 7 CFR 251.4(l), state agencies must post this uniform statewide eligibility criteria to a publicly available webpage. This information must be updated on an annual basis or whenever changes to eligibility criteria are made. Additional guidance on establishing criteria and methods for determining the eligibility of households to receive TEFAP can be found in Participant Eligibility in TEFAP (revised).

State agencies should contact their respective FNS regional office with any questions about this memorandum.

Sara Olson

Director

Policy Division

Supplemental Nutrition and Safety Programs

This TEFAP program guidance memorandum provides TEFAP state agencies information on requirements for public posting of TEFAP information.

Written Information on and Referrals to Public Assistance Programs for CSFP Participants

| DATE: | August 25, 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| POLICY NO: | FD-161: Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP) | |

| SUBJECT: | Written Information on and Referrals to Public Assistance Programs for CSFP Participants | |

| TO: | Regional Directors Supplemental Nutrition Programs | Directors CSFP State Agencies and Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs) |

Under the leadership of Secretary Brooke Rollins, USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) is prioritizing the clarification of statutory, regulatory, and administrative requirements, as well as strengthening strategies to encourage healthy choices, healthy outcomes, and healthy families. In support of these goals, FNS is issuing this memorandum to provide CSFP state agencies, including ITOs, with guidance on implementing 7 CFR § 247.14(a), which requires local agencies, as appropriate, to make referrals and provide CSFP applicants with written information on specific public assistance programs. The specific public assistance programs are:

- supplemental security income benefits (SSI);

- medical assistance under Title XIX of the Social Security Act, including medical assistance provided to qualified Medicare beneficiaries;

- the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); and

- beginning on Oct. 31, 2025, the Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP).

Methods of Information Sharing

CSFP local agencies may provide written materials in hard copy or via electronic means such as a link to a webpage, an email, or text messages to applicants.

State and Local Agency Coordination

FNS recommends that, as applicable, CSFP state agencies coordinate with the appropriate state agency for each public assistance program to ensure written information for local agency dissemination is accurate and up to date. Coordination may also occur between CSFP local agencies and entities administering the identified public assistance programs at the local level; for example, between a CSFP local agency and the local Social Security Office. For further information and applicable state or local agency contacts, see below:

- SSI

- Medicaid and Medicare

- SNAP

- SFMNP

Considerations for the Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program

SFMNP is a federal nutrition assistance program that provides low-income seniors with seasonal benefits that can be exchanged for eligible foods directly from farmers, farmers’ markets, roadside stands, and community-supported agriculture programs (CSAs). CSFP and SFMNP work in tandem to serve the low-income senior population and help meet their nutritional needs. Connecting CSFP participants with SFMNP creates new opportunities for American farmers to connect with federal nutrition assistance programs.

SFMNP is administered by state agencies, which are responsible for determining months of operation, as the program may not be available year-round. SFMNP is not available nationwide and, in states where it does operate, may not be available in all areas of a state. CSFP state and local agencies may use discretion on when it is appropriate to distribute materials and make referrals to SFMNP based on program availability.

CSFP state agencies should coordinate with SFMNP state agencies to access up-to-date information on SFMNP and determine whether the program is accepting new participants within the state. If SFMNP is not available in the applicable area(s) or the state’s SFMNP is not accepting participants, then CSFP local agencies do not need to provide written information and/or referrals to that program.

State agencies should contact their respective FNS regional office with any questions about this memorandum.

Sara Olson

Director

Policy Division

Supplemental Nutrition and Safety Programs

We are issuing this memorandum to provide CSFP state agencies, including ITOs, with guidance on implementing 7 CFR § 247.14(a), which requires local agencies, as appropriate, to make referrals and provide CSFP applicants with written information on specific public assistance programs.

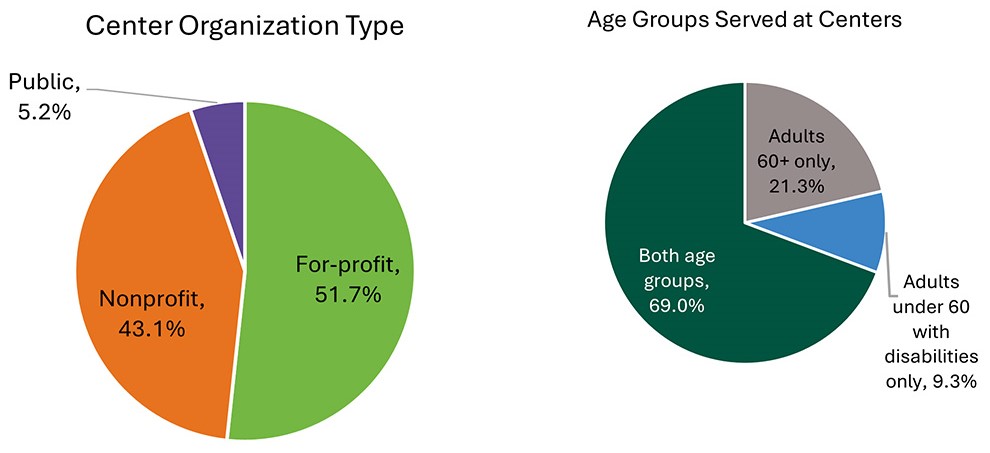

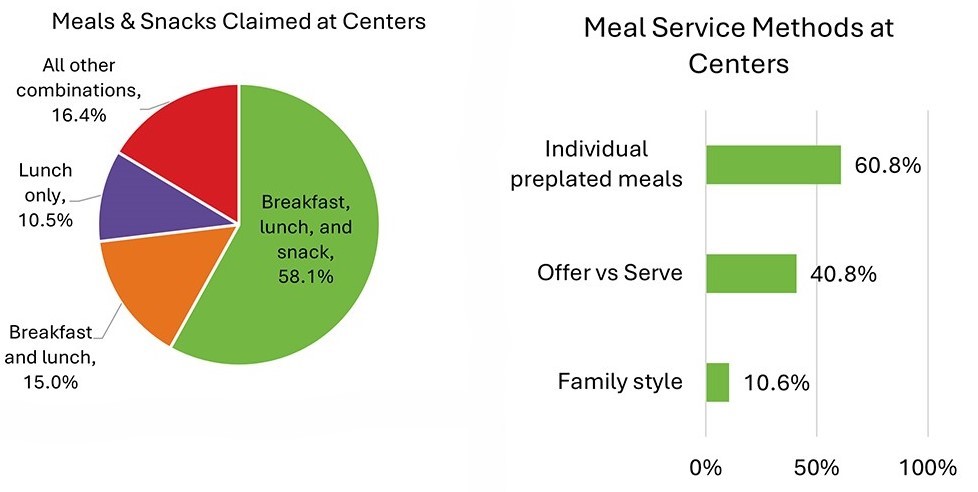

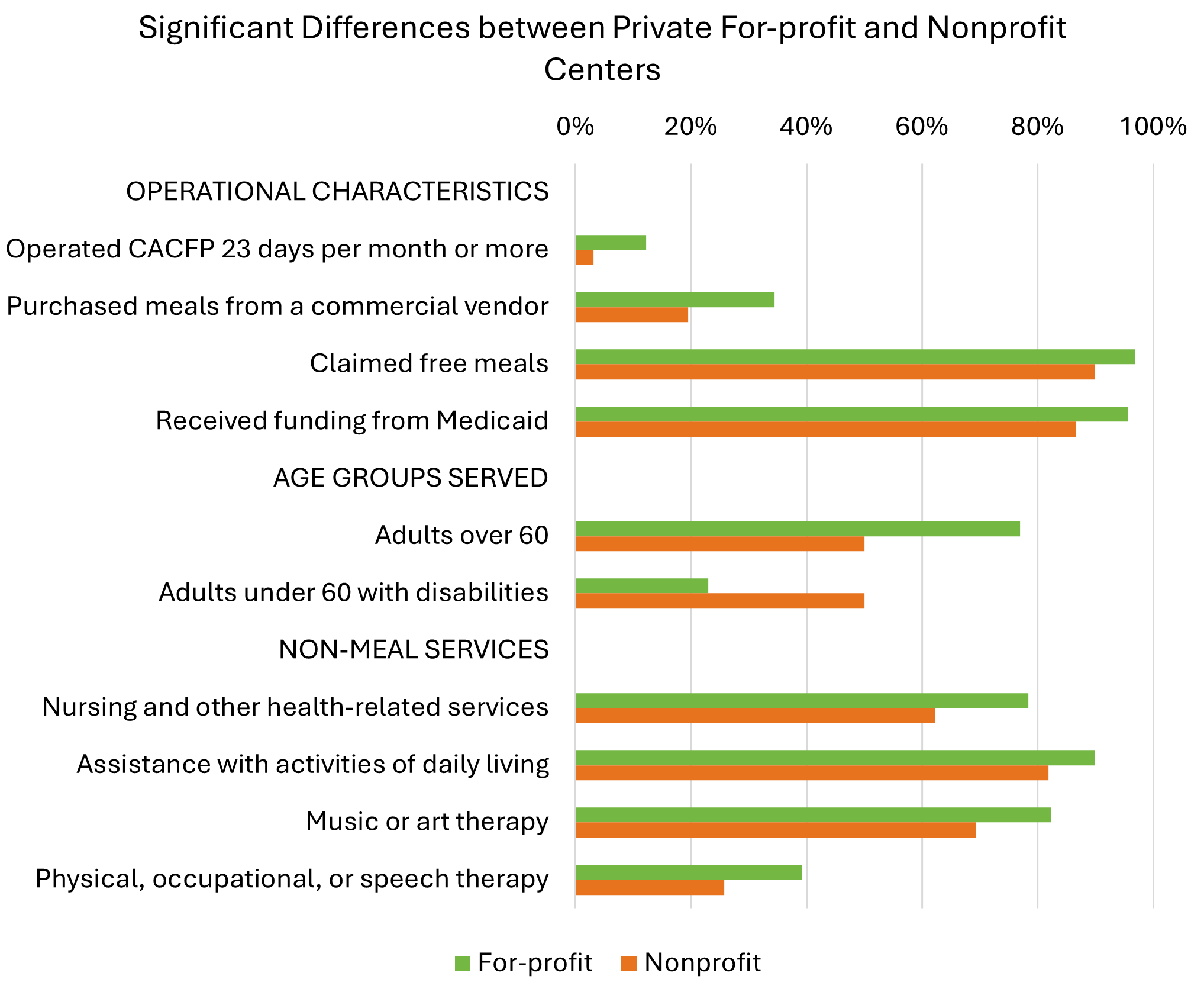

Study of Nutrition and Activity in Child Care Settings II (SNACS II)

Key Takeaway

Child care providers who participate in the USDA, Food and Nutrition Service’s Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) serve healthy meals and snacks to the children in their care. Children have better overall diets on days when they are in child care than on days when they are not.

This study reviewed early child care and before and afterschool meals of CACFP, using the Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015), to assess how well children’s diets and CACFP meals align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). Data for this study were collected during program year 2022-231 . These key findings focus on those most important to understanding the impact of CACFP, but all results can be found in the full report and appendices.

Definitions

- Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP)

The Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) reimburses child and adult care providers for serving healthy meals and snacks to individuals in their care. This report focuses only on child care providers. Reimbursements help offset the cost of preparing those meals.

- Early Child Care

In this study, early child care program providers serve children from infants through age 5 years and include child care centers, Head Start centers, and family day care homes.

- Before and Afterschool

In this study, before and afterschool program providers serve children ages 6-12 years through at-risk afterschool centers and outside-school-hours care centers.

- Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015)

This study uses the Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) to assess how well children’s diets and CACFP meals align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) (and with the 2020-2025 DGA, since no major changes were made to recommendations for individuals 2 years or older). We use the HEI to assess how nutritious a set of foods is. This study examined two sets of foods: all the foods children ate in a day and all the meals/snacks CACFP providers served in a week.

The HEI produces two types of scores: a total score and component scores. The total score ranges from 0 (the set of foods does not align with the DGA) to 100 (the set of foods fully aligns with the DGA). The total score can be broken down into component scores, which show how well the set of foods meets recommendations to eat or limit specific foods/nutrients (components). Each component has a maximum score of 5 or 10, but this study converted component scores to percentages—100% means a component had the maximum score. The two types of components are:

- Adequacy components are foods and nutrients encouraged by the DGA: total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood and plant proteins, and fatty acids.

- Moderation components are foods and nutrients that the DGA recommends limiting: refined grains, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats.

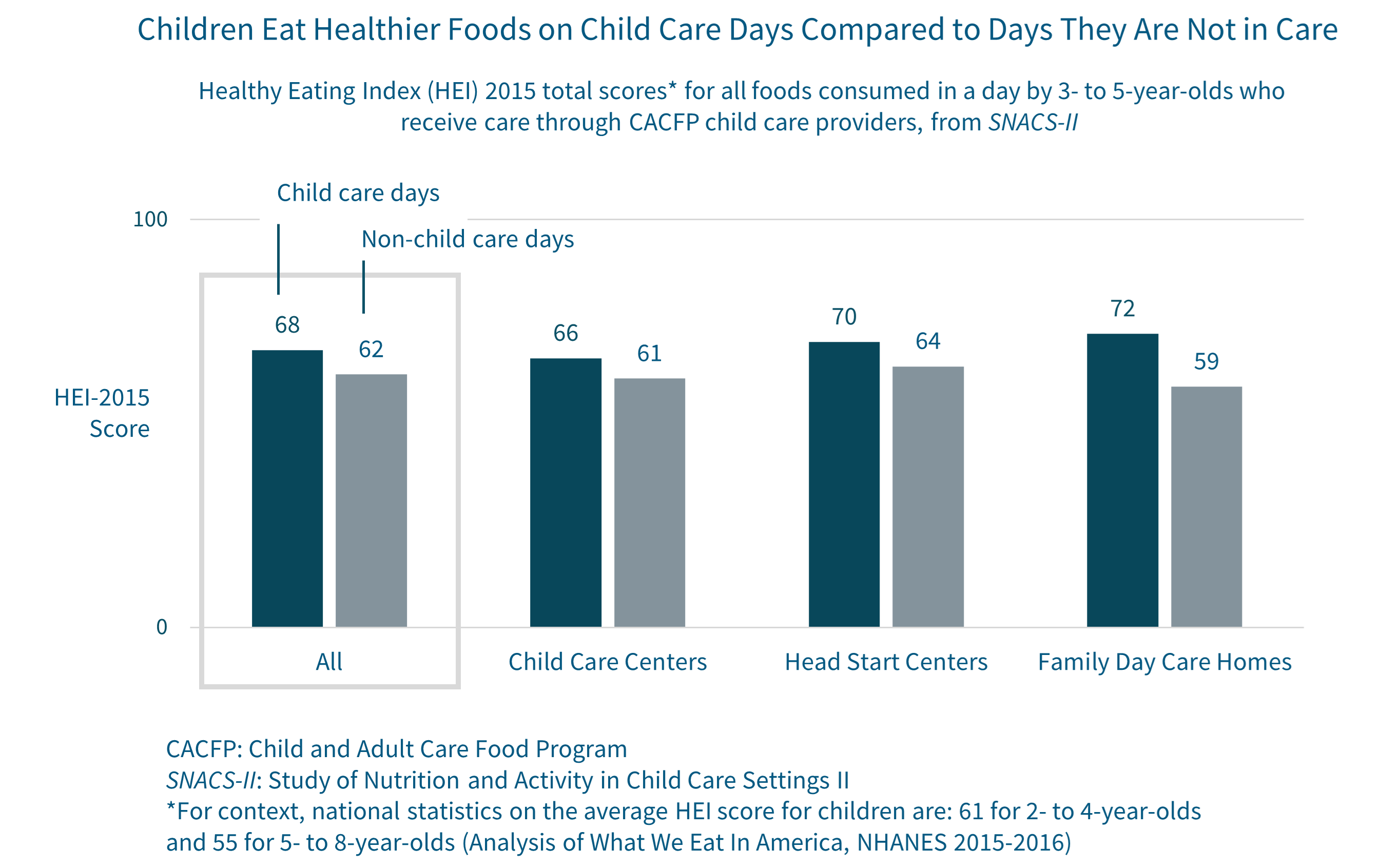

When in the care of providers participating in CACFP, children have better overall diets on days when they are in child care than on days when they are not.

With the help of parents and study staff, SNACS-II collected data on everything kids ate over the course of a day, both at child care and at home. We found that in program year 2022-23, 3- to 5-year-old children had better overall diets on days when they attended child care than on days when they did not attend. On days in child care, 3- to 5-year-olds consumed more vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and dairy compared to days not in child care. They also consumed fewer calories from saturated fats and added sugars. These differences contributed to their higher HEI total score on days when they were in child care.

The meals and snacks CACFP providers served in 2022-23 aligned with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

SNACS-II measured how the meals and snacks served by CACFP child care providers aligned with the DGA in three ways:

- USDA meal pattern requirements

- USDA requires CACFP providers to serve different meal patterns for breakfast, lunch, and snacks. Meal patterns are combinations of meal components (fruits, vegetables, grains, meats/meat alternates, and fluid milk) served in portions that vary by age. Our study found that CACFP meal patterns align with the DGA.

- In this study, most early child care programs served all the required meal components to 3- to 5-year-olds at breakfast (96%), lunch (82%), and snacks (85%). Nearly all early child care programs (99%) also met the requirement to limit fruit juice. About half (55%) met the requirement to serve whole grain-rich foods every day.

- In this study, most before and afterschool programs served all the required meal components at snack (85%) and supper (78%).

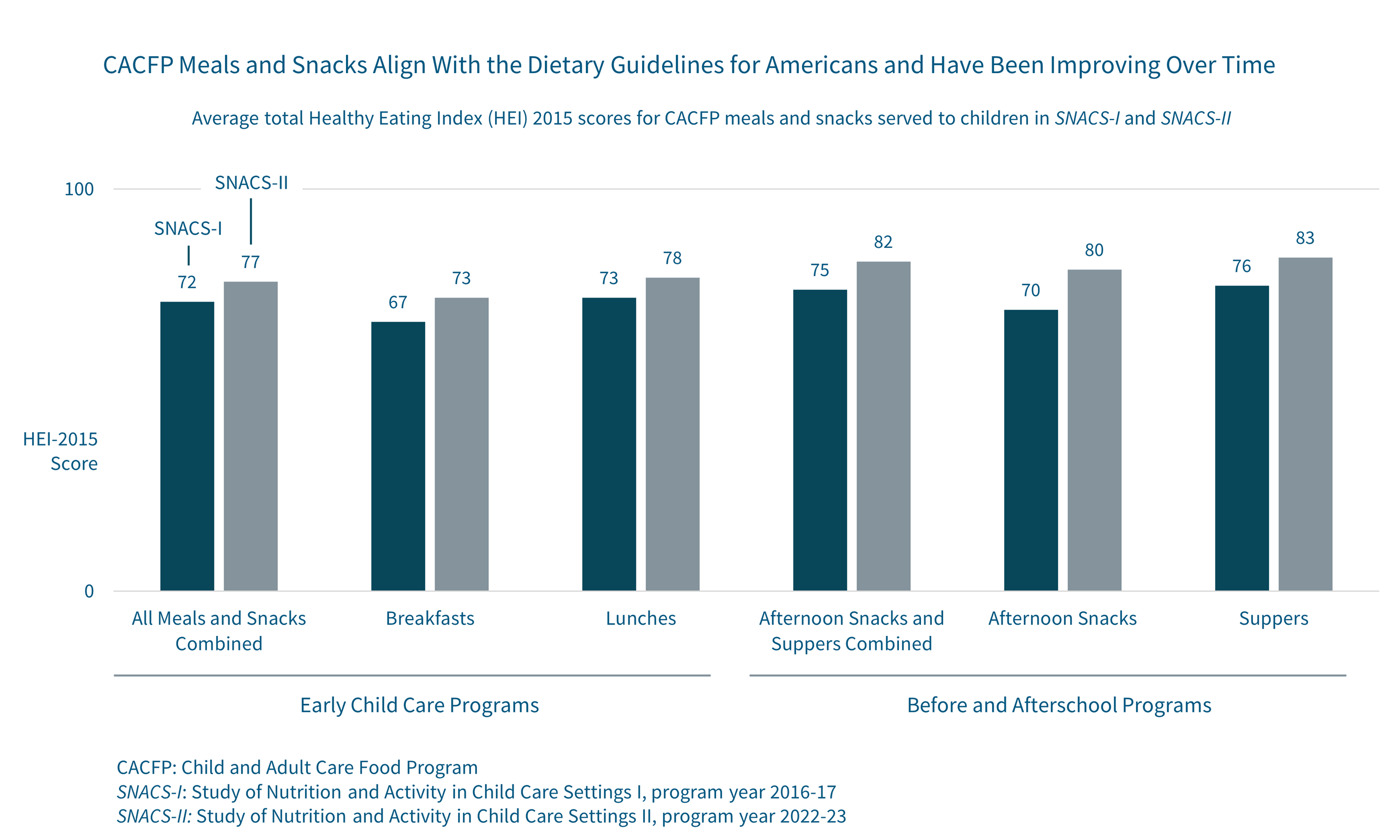

- HEI-2015 total scores over time

- HEI total scores measure how well a set of foods aligns with the DGA, with scores ranging from 0 (does not align) to 100 (aligns). People should aim to meet the dietary guidelines with their overall diet—not with every single meal—so we do not expect HEI total scores to be 100 for every single CACFP meal either. Instead, we can compare HEI total scores for CACFP meals over time to see if they are improving. We expected HEI total scores to improve from SNACS-I (collected in 2016-17) to SNACS-II (collected in 2022-23) because USDA updated the CACFP meal patterns shortly after SNACS-I to align them with the DGA.

- Note that these HEI scores for meals and snacks refer to the quality of the food served to children through CACFP, while the HEI scores in the section above refer to the food children consumed over the course of the full day.

- For children ages 3 to 5 years in early child care programs, HEI scores for breakfasts and lunches increased from SNACS-I to SNACS-II. The HEI total score for all meals and snacks combined for this age group rose from 72 in SNACS-I to 77 in SNACS-II.

- For children ages 6 to 12 years in before and afterschool programs, HEI total scores for snacks and suppers increased from 75 in SNACS-I to 82 in SNACS-II.

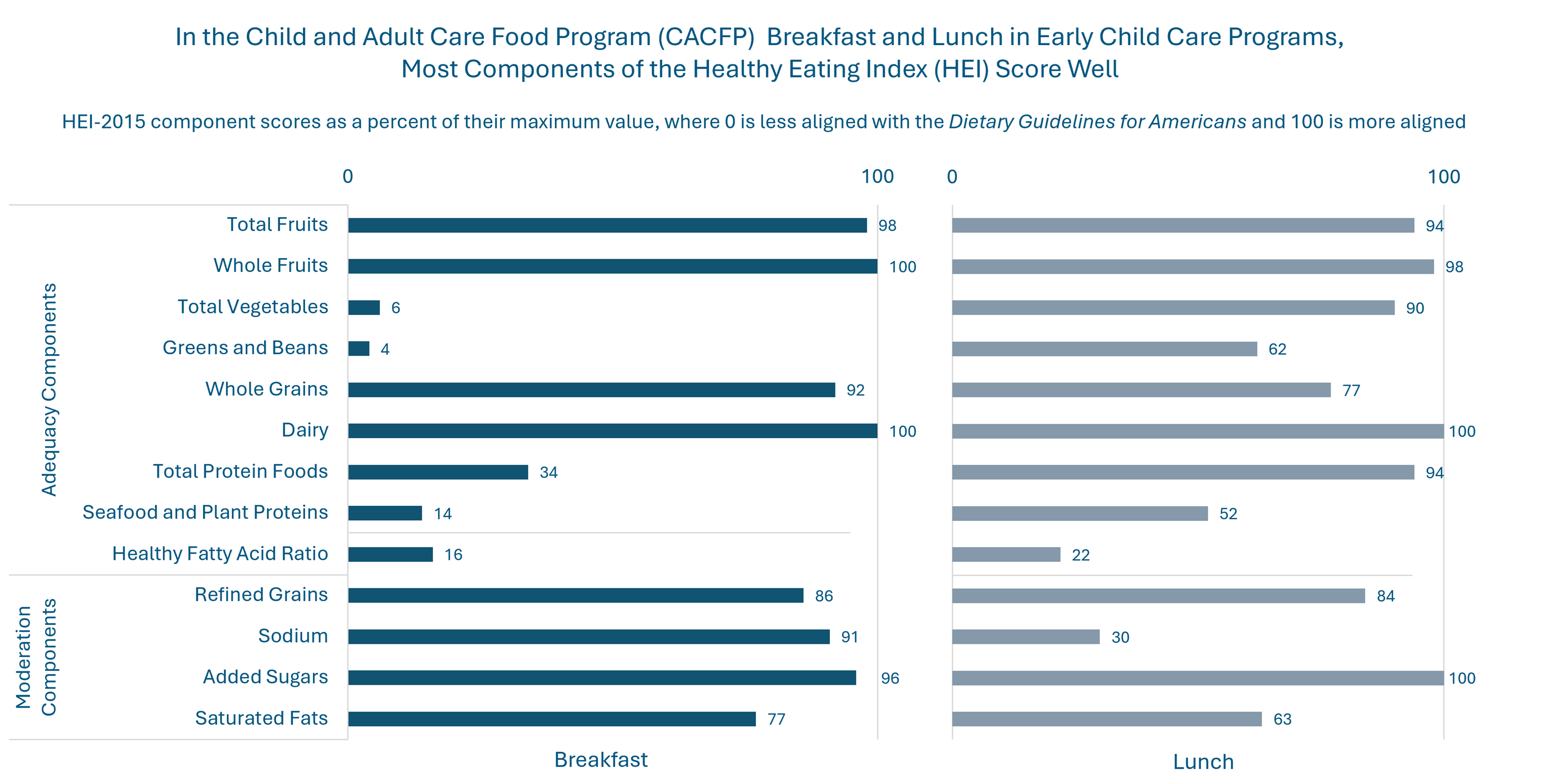

- HEI-2015 component scores

- When total HEI scores are broken down into their component parts (e.g. fruits, added sugars, etc.) for breakfast and lunch, most components scored high. Because a component may have a total of 5 or 10 points, we show component scores as a percentage of their maximum score. High component scores are good. In this study, they indicate that CACFP meals align with DGA recommendations to serve enough of some foods and nutrients (“adequacy components”) and limit others (“moderation components”). Low component scores indicate room for improvement.

- Note that the meal pattern for breakfast requires providers to serve fluid milk, a fruit or vegetable, and a grain; therefore, we expect vegetable and protein-related components to have lower scores at breakfast because they are not served as often.

- Below, we share the main findings from early child care centers in the figure and findings from before and afterschool programs in the text that follows.

- Snacks served in before and afterschool programs received high HEI component scores for total fruits (94%), saturated fats (95%), sodium (91%), and added sugars (89%), meaning snacks were consistent with DGA recommendations for those components. Scores were lower for dairy (63%) and whole grains (68%), indicating that these components are not often served as snacks since only two of five meal components are required (e.g., choice of two from fluid milk, meats/meat alternates, vegetables, fruits, and/or grains).

- Suppers served in before and afterschool programs received high HEI component scores for total fruits (98%), whole fruits (100%), dairy (100%), and added sugars (90%). The lower scores for fatty acids (42%) and sodium (50%) indicate room for improvement.

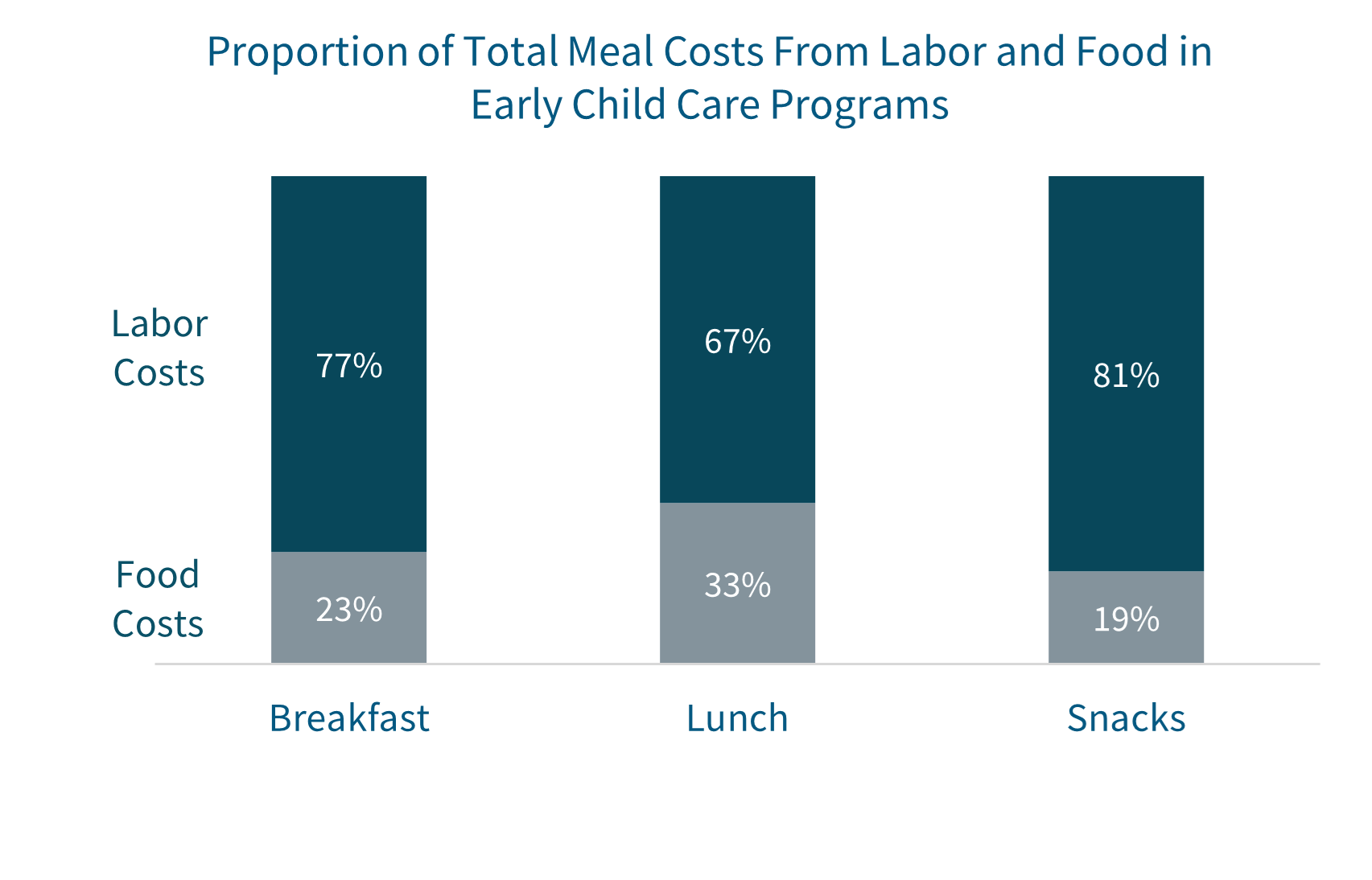

Meal reimbursement rates covered providers’ food costs but fell below total meal costs for all meal types.

USDA provides participating CACFP providers with funding (per-meal reimbursements) for meals and snacks to help offset the cost. Most of the cost to produce meals in child care centers was for labor costs rather than food costs. On average, labor costs accounted for 77% of total breakfast costs, 67% of total lunch costs, and 81% of total snack costs.

Some providers faced challenges related to CACFP.

CACFP participation: Providers reported the same top challenges to participating in CACFP in SNACS-II as they did in SNACS-I, including insufficient meal reimbursement and paperwork requirements. Although data from SNACS II indicates that CACFP reimbursements are sufficient to cover food costs, they are insufficient to cover food and labor costs. This is expected as USDA reimbursements for CACFP meals and snacks are intended to offset costs, not necessarily cover them completely.

Among SNACS-II early child care providers, 36% reported insufficient meal reimbursement as a major challenge to participation in CACFP, 31% reported it to be a minor challenge, while 33% reported it not to be a challenge. Among before and afterschool programs, 27% reported insufficient reimbursement to be a major challenge to participation, 21% reported it to be a minor challenge, while 52% reported it not to be a challenge. Paperwork requirements to receive meal reimbursement were reported as a major or minor challenge by 36% of early child care providers and 40% of before and afterschool programs, while the majority of providers reported paperwork requirements were not a challenge to participation.

Menu planning: Nearly half of providers in SNACS-II reported having no challenges planning menus that meet the CACFP meal patterns (44% of early child care programs and 48% of before and afterschool programs). Limited access to foods that fit the requirements was the most reported challenge to meeting nutritional requirements (24% of early child care programs and 27% of before and afterschool programs).

Why did FNS do this study?

SNACS-II is the second study in the SNACS study series. The series collects data about CACFP child care providers, the children they care for, the meals and snacks they serve, the cost of producing those meals and snacks, and the physical activity opportunities they provide. We use the data to learn important information about CACFP, such as how nutritious CACFP meals and snacks are and how healthy children’s diets are on the days when they are and are not in child care.

Shortly after SNACS-I data was collected for program year 2016-17, USDA updated the CACFP meal pattern requirements for the first time since 1968 (when the program began). The updated meal patterns require a larger variety of fruits and vegetables, more whole grains, and less added sugars and saturated fats. With data collected in program year 2022-23, SNACS-II helps us understand how the nutritional quality of CACFP meals and snacks and children’s diet quality may have changed with the new meal pattern requirements and provides an update on other key findings from the first study.

How did FNS do this study?

SNACS-II used similar methods to SNACS-I so we could compare key outcomes from program years 2016-17 (SNACS-I) and 2022-23 (SNACS-II).

SNACS-I and SNACS-II studied providers and children from early child care programs and before and afterschool programs. The providers and children in the SNACS studies were nationally representative, which means they had similar characteristics to all the CACFP child care providers and children in the United States. We estimated nationwide findings by scaling up the data we collected from our nationally representative study participants.

The study used surveys to collect information about the topics of interest:

- Characteristics and food service practices of CACFP providers

- Nutrient profiles of CACFP meals and snacks

- Dietary intake of children during child care and non-child care days

- Characteristics of children and families served by CACFP providers

- Infant feeding practices, infant food intake, and infants’ activity levels while in child care

- Opportunities for physical activity in programs participating in CACFP

- Plate waste

- The cost of producing a CACFP breakfast, lunch, supper, and snack

The study used the Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) to assess children’s diet quality and the nutritional quality of CACFP meals and snacks. The HEI total score measures how well a set of foods aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, with scores ranging from 0 (does not align) to 100 (aligns). In this study, we collected data about two sets of foods:

- All the food children ate in 24 hours: This set of foods lets us assess children’s diet quality, or how well children’s diets aligned with the DGA. We compared HEI scores on days when children did and did not attend child care to learn how CACFP meals and snacks contribute to children’s overall diet quality.

- All the food served in CACFP meals and snacks in a week: This set of foods let us assess the nutritional quality of CACFP meals and snacks as they were served, or how well the meals and snacks aligned with the DGA. We compared HEI scores in SNACS-I and SNACS-II to assess change over time.

The HEI total score is made up of 13 component scores (for more detail, see the HEI drop down box under “Definitions”). Individual components have a maximum score of five or ten but, for purposes of this study, component scores are shown as a percentage of the maximum score for that component. Therefore, a component score of 100% indicates that a diet or meal is fully aligned with DGA recommendations for that component. We used HEI component scores to assess the nutritional quality of CACFP meals and snacks.

Suggested Citation

Forrestal, S., Boyle, M., Bleiweiss-Sande, R., Franckle, R., Hu, M., Kali, J., Neelan, T., and Niland, K. (2025). Study of Nutrition and Activity in Child Care Settings II (SNACS-II). Prepared by Mathematica, AG-3198-1-9F-0151. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support, Project Officer: Constance Newman. Available online at .

1 In CACFP, program years align with the federal fiscal year. For example, in this case, program year 2022-23 ran from Oct. 1, 2022 through Sept. 30, 2023.

SNACS-II studied child care providers who participate in the Child and Adult Care Food Program. This study found that these providers serve healthy meals and snacks to the children in their care. Children have better overall diets on days when they are in child care than on days when they are not.

WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2: Ninth Year Report

The WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2 (WIC ITFPS-2), also known as the "Feeding My Baby Study," is the only national study to analyze the long-term impact of WIC by gathering information on caregivers and children over the first nine years of the child's life after enrollment in WIC, regardless of their continued participation in the program.

WIC Participation Is Associated With Declining Rates of Hunger